Recent policy changes have boosted the role of advanced practice providers (APPs) in oncology clinical trials, but education is needed to enhance accrual and improve conduct of clinical trials, according to Christa Braun-Inglis, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, AOCNP, a nurse practitioner and assistant researcher at the University of Hawai’i Cancer Center, in Honolulu, and an advocate for expanding the role of APPs in oncology clinical trials.

When Braun-Inglis began working on oncology clinical trials, APPs were not permitted to sign cancer treatment orders on National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored trials, even if they were authorized to do so by their institutions and state and local laws. APPs were also not allowed to enroll patients in NCI trials involving medications as independent providers; they were only allowed to enroll under a physician.

Then in August 2020, an important policy change was announced: APPs would be able to enroll their patients on supportive care trials through NCI. Specifically, nurses with a PhD, DNP, or master’s-level preparation, training, and NCI trial-related experience would be qualified to serve as chairs, cochairs, and local investigators to consent and enroll patients as well as prescribe/write orders for study agents for select NCI trials involving cancer prevention, symptom management, behavioral intervention, and cancer care delivery protocols.

On Sept. 7, 2021, another policy change was announced. Qualified APPs—those who are registered as nonphysician investigators (NPIVRS) as well as licensed and qualified per their organizational and state statutes—would be allowed to sign patient orders for study agents, including investigational new drugs (INDs) and standard of care agents, without a physician cosignature for NCI-sponsored trials. APPs would be required to register as nonphysician investigators with NCI, a registration which must be renewed annually.

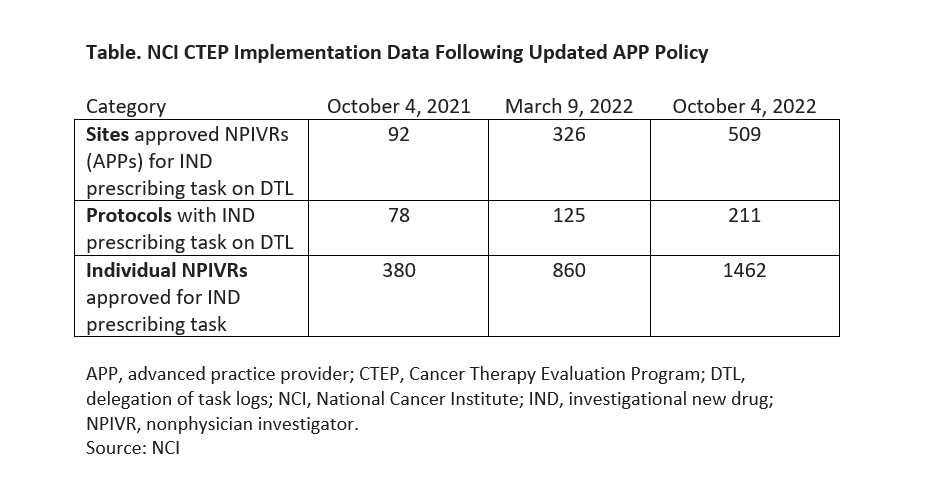

Within 5 months of the policy change on prescribing, NCI reported the following metrics (see Table for latest data):

- More than 1,000 APPs registered as NPIVRS;

- 418 sites implemented the policy to allow NPIVRs to sign orders for INDs;

- 800 patients were enrolled by NPIVRs to NCI-sponsored supportive care delivery trials; and

- 860 NPIVRs were approved for IND prescribing.

Although NCI is the largest sponsor of oncology clinical trials, Braun-Inglis said it will be important for APPs to have the same privileges with regard to industry-sponsored trials. “What I’ve told industry colleagues is you have to look at the language on your protocol. There’s a lot of language within protocol that talks about physician investigators. Think about changing that language and being clear how the APP can function and don’t hold them back. Actually, the FDA does not even require the primary investigator of a study to be a physician,” she said.

“If you’re going to hold the APP back, it’s going to slow down your research because we are so integrated in everyday clinical practice now. If you’re not engaging us, educating us, and allowing us to do clinical research, it’s a huge barrier for the success of your research protocol.”

Allowing APPs to prescribe for oncology clinical trials and to enroll their own patients in supportive therapy and symptom management clinical trials are examples of policy changes that Braun-Inglis and her colleagues had called for in an article published in the Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology. Published in 2022, the authors presentedsurvey results addressing the attitudes, beliefs, and role of APPs in oncology clinical trials. In addition to policy changes, the authors recommended enhancing APP clinical trial training for those in practice today as well as within graduate training programs, and organizational support for the APP role in clinical trials.

APP Education in Oncology Clinical Trials

“First and foremost, there is a need for education, and there’s a need to have resources and educational activities for APPs to learn how to be investigators on clinical trials,” Braun-Inglis said, explaining that, unlike their physician counterparts who have had some exposure to research during their residencies and fellowships, many APPs have not been exposed to research during their training.

Braun-Inglis distinguishes between the education needed for APPs to work as investigators on clinical trials—following the protocol, grading and attributing adverse events, managing side effects, managing dose modifications and dose changes, measuring tumors using RECIST criteria—and developing and leading clinical research when it is not necessary to be collaborating with an oncologist.

“There is that basic need for education for us to be responsible and good investigators, which is very important. Then there’s that next piece of leadership,” said Braun-Inglis. Noting that APPs work in collaborative practice models, Braun-Inglis said most APPs have a lot of autonomy in symptom management and supportive care. “That’s where I see a lot of growth,” she said. “We should really start to enroll our own patients in those trials, separate from the collaborating oncologist. If we’re taking a lead role in the clinic, we should be taking a lead role in the research.”

Braun-Inglis is working with a group from the NCI/NCI Community Oncology Research Program research bases to develop a resource manual for APPs participating in oncology clinical trials supported by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-American College of Radiology Imaging Network, and received a 5-year grant through the Southwest Oncology Group focusing on APP engagement cancer clinical trials to provide education, assess institutional policies, and examine workflows across the NCI National Clinical Trials Network.

She also developed a mentorship project to train APPs as subinvestigators, enrolling investigators and site primary investigators on cancer control, symptom management, and Cancer Care Delivery Research trials across Hawaii.

Braun-Inglis praised the Advanced Practitioner Society for Hematology and Oncology (APSHO) for including a module on clinical trials in their cancer therapy prescribing course. “I think that’s a great primer,” said Braun-Inglis, who is chair of the APSHO Research and Quality Improvement Committee. She is working with APSHO to set up a clinical research toolkit for APPs. Ideally, she said she wants to have an educational program for APPs that’s readily available that would cover how to be an investigator as well as how to develop and lead clinical research protocols.

For more information

Braun-Inglis, C., Boehmer, L. M., Zitella, L. J., Hoffner, B., Shvetsov, Y. B., Berenberg, J. L., Oyer, R. A., & Benson, A. B., 3rd (2022). Role of oncology advanced practitioners to enhance clinical research. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, 13(2), 107–119.

Braun-Inglis, C., Williams, E.L., Macchiaroli, A., Denicoff, A., Gerber, D.E. (2022). Better late than never: fully incorporating oncology advanced practice providers into cancer clinical trials. JCO Oncology Practice, 18(11), 729–732.

Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, September 7). Memorandum: Guidance and update on advanced practice providers writing study agent orders on clinical trials supported by the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP).https://ctep.cancer.gov/investigatorResources/docs/Memorandum-Study-Agent-Ordering-Update-Sept.07.2021-FINAL.pdf

NCI DCP & DCCPS NCORP Guidelines. (2020, August 12). Advanced practice nurse roles in DCP trials and DCCPS studies. https://webcast.imsts.com/sites/webcast.imsts.com/files/2021-04/DCP%20-%20DCCPS%20Guideline%20for%20Use%20of%20APPs%20%20081220.pdf

National Cancer Institute. (2021, September 7). Advanced practice providers (APPs) & investigational agent orders: update on CTEP policy and implementation. https://ctep.cancer.gov/investigatorResources/docs/Slide_Set_on_Advanced_Practice_Providers_Policy.pdf