Aileen Anglin, APRN, ACNP-BC, AOCNP

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for about 15% of all lung cancers in the United States. It is a type of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that is almost exclusively associated with cigarette smoking (~98% of cases). It has a rapid doubling time and early development of widespread metastatic disease, with the most common sites of metastasis being the contralateral lung, liver, bones, adrenal glands, and brain. It is notorious for high responsiveness to treatment, but most patients will relapse with broadly resistant disease within months of initial therapy.1-3

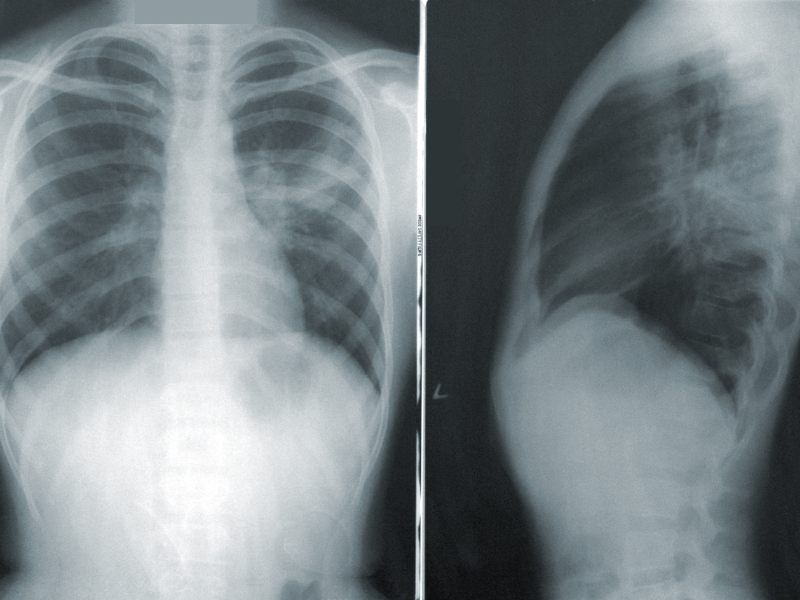

Staging for SCLC is typically grouped into limited- or extensive-stage disease. Limited stage (LS-SCLC) means disease is confined to the ipsilateral hemithorax, can be included in a single radiotherapy port, and no malignant pleural or pericardial effusion is present. Disease not meeting the criteria for LS-SCLC is considered extensive stage (ES-SCLC). About 70% of patients diagnosed with SCLC will have extensive-stage disease at the time of diagnosis, with 10% to 25% having brain metastases at initial presentation and an additional 40% to 50% will develop brain metastases later. The 5-year overall survival rate for ES-SCLC is about 3%.1,4

Therapeutic Breakthrough

For over 30 years, the main therapy for ES-SCLC has remained the same with platinum-etoposide doublet chemotherapy being the preferred regimen.2 Then, in 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq, Genentech) in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for the first-line treatment of ES-SCLC after it showed a 30% improvement in median overall survival (OS) over placebo plus carboplatin and etoposide in the IMpower133 trial.5 Durvalumab (Infinzi, AstraZeneca) was later approved in the 2020 in the CASPIAN trial for the same indication.6 Clinical trials are ongoing to determine if human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors (such as ipilimumab [Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb] and tremelimumab [Imjudo, AstraZeneca]) can become approved standard treatment options in the future.7

Despite the addition of immunotherapy, almost all patients will develop progression eventually. Patients have platinum-sensitive disease if progression occurs over 90 days from completion of frontline platinum therapy. Patients with a chemotherapy-free interval (CTFI) of greater than 6 months can be rechallenged with the same frontline regimen. If CTFI is 3 to 6 months, rechallenging with original regimen can be considered. However, if disease recurs prior to 90 days from completion, then they are deemed platinum resistant and should be given second-line therapy.3,8 Up until 2020, the only approved second-line option available was topotecan, a topoisomerase 1 inhibitor. Although topotecan showed an OS benefit over best supportive care of 25.9 weeks vs 13.9 weeks, it is associated with significant myelosuppression and 6% toxic deaths.9

In June 2020, lurbinectedin (Zepzelca, Jazz Pharmaceuticals) was approved for ES-SCLC after failure of platinum-based therapy. The FDA granted accelerated approval based on the results of a phase 2 basket trial that showed overall response rates of 35.2% and response duration of 5.2 months. The platinum-sensitive group had a response rate of 45% compared to 22% in the platinum-resistant group. Based on these positive results and a better safety profile, lurbinectedin has become the preferred second-line regimen over topotecan.9

Targeted Therapies: Not Yet an Option

Unlike its non-small cell lung counterpart, targeted therapy is yet to be an option for SCLC due to the lack of identifiable driver mutations. In most SCLC cases, there is loss or inactivation of the tumor suppressor genes tumor protein p53 (TP53) and retinoblastoma 1 (RB1). Unfortunately, there are no drugs available to target either of these genes. Genomic sequencing has also shown recurrent amplification or loss of multiple other genes, but the significance is yet to be determined.10

Four major subtypes of SCLC have been identified according to the differential expression of transcription factors achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1), neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (NEUROD1), and POU class 2 homeobox 3 (POU2F3) or low expression of all 3 transcription factor signatures accompanied by an Inflamed gene signature. These are referred to as SCLC-A, N, P, and I, respectively. Studies are ongoing to help determine if each subtype is more responsive to different classes of drugs, as well as identifying if subtype crossover contributes to resistance. For example, in vitro studies show that SCLC-I (subtype I) appeared to benefit most from immunotherapy whereas subtype P (SCLC-P) was very sensitive to poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.11

In 2021, trilaciclib (Cosela, G1 Therapeutics) was approved as a supportive care therapy for ES-SCLC. Trilaciclib is a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor that is given as an intravenous infusion prior to each dose of platinum-etoposide or topoetecan to decrease the incidence of myelosuppression and prevent dose delays or reductions. Most common side effects were fatigue, electrolyte imbalances, elevated liver enzymes, headache, and pneumonia.12

With the approval of immunotherapy and emerging data of SCLC subtypes, the treatment landscape looks prosperous in what was once an otherwise barren region. Individualized therapy may not be very far away and hope for better outcomes in SCLC is on the horizon.

References

- American Cancer Society (2023). Lung Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

- Morgensztern, D, Ghobadi, A., and Ramaswamy, G. (2022). The Washington Manual of Oncology.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 3.2023.

- Byers, L, and Gay, C. (2021). Pathobiology and staging of small cell carcinoma of the lung. UpToDate.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves atezolizumab for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-atezolizumab-extensive-stage-small-cell-lung-cancer.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves durvalumab for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-durvalumab-extensive-stage-small-cell-lung-cancer.

- Walia HK, Sharma P, Singh N, Sharma S. (2022). Immunotherapy in Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment: A Promising Headway for Future Perspective. Current treatment options in oncology. 23(2):268-294.

- Lara, P. N., Jr, Moon, J., Redman, M. W., Semrad, T. J., Kelly, K., Allen, J. W., Gitlitz, B. J., Mack, P. C., & Gandara, D. R. (2015). Relevance of platinum-sensitivity status in relapsed/refractory extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer in the modern era: a patient-level analysis of southwest oncology group trials. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, 10(1), 110-115.

- Manzo, A., et al. (2022). Lurbinectedin in small cell lung cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 12: 932105.G1 Therapeutics (2021). Cosela Prescribing Information.

- Drapkin, B, and Rudin, C. (2021). Advances in Small-Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC). Translational Research. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 11(4), 1-28.

- Gay, C. M., Stewart, C. A., Park, E. M., Diao, L., Groves, S. M., Heeke, S., Nabet, B. Y., Fujimoto, J., Solis, L. M., Lu, W., Xi, Y., Cardnell, R. J., Wang, Q., Fabbri, G., Cargill, K. R., Vokes, N. I., Ramkumar, K., Zhang, B., Della Corte, C. M., Robson, P., … Byers, L. A. (2021). Patterns of transcription factor program and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer cell, 39(3), 346-360.e7.

- G1 Therapeutics (2021). Cosela Prescribing Information.